The Nature of Business-Level Competitive Strategies

A competitive business-level strategy is a plan to addresses the question of how a firm will position itself within an industry and compete with other firms while doing so.

Companies pursue a competitive business-level strategy to utilize competitive advantages that enable them to outperform rivals and achieve above-average returns within a particular competitive scope.

A competitive business-level strategy consists of 2 dimensions.

The first dimension answers the question of whether the company should compete head-to-head with major competitors the biggest share of the market, or should it focus on a niche in which we can satisfy a profitable segment of the market?

The second dimension answers the question of whether the company competes on the basis of lower cost, or should it differentiate products and services on some basis other than costs, such as quality, or service?

First Dimension of Competitive Business-Level Strategies

The first dimension is a firm’s source of competitive advantage.

This dimension involves whether a firm tries to gain an edge over rivals by keeping costs down or by offering something unique in the market.

In this dimension, there are generally 2 basic competitive strategies for outperforming other organizations in a particular industry: (1) lower cost and (2) differentiation.

A lower-cost strategy is the ability of a company to design, produce, and market a comparable product more efficiently than its competitors. Having lower costs results from the firm’s ability to perform activities more efficiently than rivals.

Differentiation strategy is the ability of a company to provide unique and superior value to the buyer in terms of product quality, special features, or after-sale service. Having able to differentiate indicates the firm’s capacity to perform different activities.

Thus, based on the nature and quality of its internal resources, capabilities, and core competencies, a firm seeks to form either a cost-competitive advantage or a distinctiveness competitive advantage as the basis for implementing its competitive business-level strategy.

Second Dimension of Competitive Business-Level Strategies

The second dimension is firms’ scope of operations.

This dimension involves whether a firm tries to target customers in general or whether it seeks to attract just a segment of customers.

The company has to determine its competitive scope, which is the breadth of the organization’s market. The firm must select the range of product varieties it will produce, the distribution channels it will employ, the types of buyers it will serve, or the geographic areas in which it will sell.

In this dimension, the 2 types of target markets are (1) broad market and (2) narrow market segment.

Firms serving a broad market seek to use their capabilities to create value for customers on an industry-wide basis.

Firms serving a narrow market segment intend to select a segment or group of segments in the industry and tailors their strategy to serving them to the exclusion of others.

In general, this should reflect an understanding of the organization’s strengths and weaknesses. This will determine whether the firm should select a broad target, as at the middle of the mass market, or a narrow target, as at a specific market niche.

Variations of Competitive Business-Level Strategies

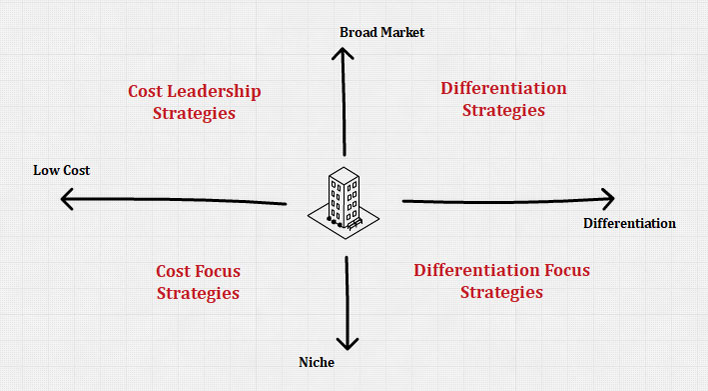

Combining these 2 dimensions, there are 4 variations of competitive business-level strategies that firms should focus on.

They are (1) cost leadership, (2) differentiation, (3) cost focus, and (4) differentiation focus.

Each of these strategies can effectively be used to allow a firm to position itself favorably relative to the competitive forces in the industry, thus establish and defend its desired strategic position against competitors.

They imply different organizational arrangements, control procedures, and incentive systems. Larger firms with greater access to resources typically compete on a cost leadership and/or differentiation basis, whereas smaller firms often compete on a cost focus/differentiation focus.

Understanding the differences that underlie these strategies is important because different strategies offer different value propositions to customers. A firm focusing on cost leadership will have a different value chain configuration than a firm whose strategy focuses on differentiation.

Besides the main 4 variations of competitive business-level strategies, firms can find themselves pursuing other variations.

A firm could also strive to develop an integrated cost leadership/differentiation strategy as the foundation for serving a target customer group that is larger than a narrow market segment but not as comprehensive as a broad (or industry-wide) customer group.

In rare cases, firms can follow a best-cost strategy because they are able to offer both low prices and unique features that customers find desirable. Firms that are not able to offer low prices or appealing unique features are referred to as stuck-in-the-middle.

None of the competitive business-level strategies is inherently or universally superior to the others.

The effectiveness of each strategy is contingent both on the opportunities and threats in a firm’s external environment and on the strengths and weaknesses derived from the firm’s resource portfolio.

It is critical, therefore, for the firm to select a business-level strategy that represents an effective match between the opportunities and threats in its external environment and the strengths of its internal organization based on its core competencies.

Competitive business-level strategies are also called generic strategies because all businesses or industries can pursue them, regardless of whether they are manufacturing, service, or nonprofit enterprises.

Variation 1: Cost Leadership

This is a low-cost competitive strategy that aims at a broad mass market. It requires avoidance of marginal customer accounts, and cost minimization in areas like R&D, service, salesforce, or advertising.

The basic idea is to underprice competitors and thereby gain market share and sales, entirely driving some competitors out of the market.

Because the cost is low, the company can charge a lower price for its products than its competitors and still make a profit. Low costs also allow the firm to continue earning profits during a time of heavy competition. The organization can have higher bargain power because it is buying in large quantities. The new entrants will have to match the cost disadvantage before they can break the barrier of entry to enter the market and still is profitable.

A successful cost leadership strategy usually permeates the entire firm, as evidenced by high efficiency, low overhead, limited perks, intolerance of waste, intensive screening of budget requests, wide spans of control, rewards linked to cost containment, and broad employee participation in cost control efforts.

Striving to be the low-cost producer in an industry can be especially effective when the market is composed of many price-sensitive buyers when there are few ways to achieve product differentiation when buyers do not care much about differences from brand to brand, or when there are a large number of buyers with significant bargaining power.

Companies employing a cost leadership strategy must achieve their competitive advantage in ways that are difficult for competitors to copy or match.

If rivals find it relatively easy or inexpensive to imitate the leader’s cost leadership methods, the leaders’ advantage will not last long enough to yield a valuable edge in the marketplace.

To employ a cost leadership strategy successfully, a firm must ensure that its total costs across its overall value chain are lower than competitors’ total costs.

A firm must be careful not to use such aggressive price cuts that their own profits are low or non-existent. Constantly be mindful of cost-saving technological breakthroughs or any other value chain advancements that could erode or destroy the firm’s competitive advantage.

A number of cost elements affect the relative attractiveness of this strategy, including economies or diseconomies of scale achieved, learning and experience curve effects, the percentage of capacity utilization achieved, and linkages with suppliers and distributors.

Other cost elements to consider include the potential for sharing costs and knowledge within the organization, R&D costs associated with new product development or modification of existing products, labor costs, tax rates, energy costs, and shipping costs.

There are 2 methods a firm can drive its total cost lower than competitors’ total costs:

Method 1: Perform value chain activities more efficiently than rivals and control the factors that drive the costs of value chain activities. Such activities could include altering the plant layout, mastering newly introduced technologies, using common parts or components in different products, simplifying product design, finding ways to operate close to full capacity year-round, and so on.

Method 2: Revamp the firm’s overall value chain to eliminate or bypass some cost-producing activities. Such activities could include securing new suppliers or distributors, selling products online, relocating manufacturing facilities, avoiding the use of union labor, and so on.

Cost leadership strategy can be especially effective under the following 7 conditions.

They are: (1) When price competition among rival sellers is especially vigorous; (2) When the products of rival sellers are essentially identical and supplies are readily available from any of several eager sellers; (3) When there are few ways to achieve product differentiation that have value to buyers; (4) When most buyers use the product in the same ways; (5) When buyers incur low costs in switching their purchases from one seller to another; (6) When buyers are large and have significant power to bargain down prices; and (7) When industry newcomers use introductory low prices to attract buyers and build a customer base.

There are certain risks related to pursuing a cost leadership strategy.

Some of the major risks are (1) competitors may imitate the strategy, thus driving overall industry profits down; (2) technological breakthroughs in the industry may make the strategy ineffective; and (3) buyer interest may swing to other differentiating features besides price.

Variation 2: Differentiation

This aims at the broad mass market and involves the creation of a product and service that is perceived as unique throughout the industry. The company can then charge a premium for its products and services.

Special features that differentiate one’s product can include superior service, spare parts availability, engineering design, product performance, useful life, gas mileage, or ease of use.

A differentiation strategy should be pursued only after a careful study of buyers’ needs and preferences to determine the feasibility of incorporating one or more differentiating features into a unique product that features the desired attributes.

Differentiation does not guarantee a competitive advantage, especially if standard products sufficiently meet customer needs or if rapid imitation by competitors is possible. Durable products protected by barriers to quick copying by competitors are best. Successful differentiation can mean greater product flexibility, greater compatibility, lower costs, improved service, less maintenance, greater convenience, or more features.

A firm, therefore, must be careful when employing a differentiation strategy. Buyers will not pay the higher differentiation price unless their perceived value exceeds the price they are paying. Based on such matters as attractive packaging, extensive advertising, quality of sales presentations, quality of Web site, list of customers, professionalism, size of the firm, and/or profitability of the company, perceived value may be more important to customers than the actual value.

Differentiation strategy is also great at build brand loyalty.

A successful differentiation strategy allows a firm to charge a higher price for its product and to gain customer loyalty because consumers may become strongly attached to the differentiation features.

At high brand loyalty, customers are less sensitive to price. New firms entering the market will also need to differentiate themselves in some way to build their own distinctive competence and compete successfully. Differentiation strategies generally create a better barrier of entry than low-cost strategies.

The most effective differentiation bases are those that are hard or expensive for rivals to duplicate.

Competitors are continually trying to imitate, duplicate, and outperform rivals along with any differentiation variable that has yielded a competitive advantage. To the extent that differentiating attributes are tough for rivals to copy, a differentiation strategy will be especially effective, but the sources of uniqueness must be time-consuming, cost-prohibitive, and simply too burdensome for rivals to match.

Differentiation opportunities exist or can potentially be developed anywhere along the firm’s value chain, including supply chain activities, product R&D activities, production and technological activities, manufacturing activities, human resource management activities, distribution activities, or marketing activities.

Common organizational requirements for a successful differentiation strategy include strong coordination among the R&D and marketing functions and substantial amenities to attract scientists and creative people. Firms can pursue a differentiation strategy based on many different competitive aspects.

A differentiation strategy can be especially effective under the following 4 conditions.

They are: (1) When there are many ways to differentiate the product or service and many buyers perceive these differences as having value; (2) When a buyer needs and uses are diverse; (3) When few rival firms are following a similar differentiation approach; (4) When technological change is fast-paced and competition revolves around rapidly evolving product features.

There are certain risks related to pursuing a differentiation strategy.

One major risk associated with a differentiation strategy is that the unique product may not be valued highly enough by customers to justify the higher price. When this happens, a cost leadership strategy easily will defeat a differentiation strategy.

The second major risk of pursuing a differentiation strategy is that competitors may quickly develop ways to copy the differentiating features. Firms thus must find durable sources of uniqueness that cannot be imitated quickly or cheaply by rival firms.

Variation 3: Cost Focus

This is a low-cost competitive strategy that focuses on a particular buyer group or geographic market and attempts to serve only this niche.

In using cost focus, the company seeks a cost advantage in its target segment.

A successful cost focus strategy depends on an industry segment that is of sufficient size, has good growth potential, and is not crucial to the success of other major competitors. Cost focus strategies are most effective when consumers have distinctive preferences or requirements and when rival firms are not attempting to specialize in the same target segment.

Variation 4: Differentiation Focus

A company using a differentiation focus will seek differentiation in a target market segment.

This strategy variation is great when a company can focus its efforts to better serve the special needs of a narrow strategic target, which can be a particular buyer group, product line segment, or geographic market.

Risks of pursuing a differentiation focus strategy include (1) the possibility that numerous competitors will recognize the successful focus strategy and copy it; (2) consumer preferences will drift toward the product attributes desired by the market as a whole.

Resources

Further Reading

- Business Level or Generic or Competitive Strategies (mbaknol.com)

- Types of Business Level Strategies to Improve Your Company (indeed.com)

- Porter’s Generic Strategies (quickmba.com)

- Basic Generic Competitive Business Strategies (careercliff.com)

- Introduction to Porter’s Generic Strategies (getlucidity.com)

- Porter’s Generic (Competitive) Strategies (businessballs.com)

Related Concepts

- Business Level Strategy

- Cost Leadership Strategy

- Differentiation Strategy

- Focus Strategy

- Integrated Best Cost Strategy

References

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2019). Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases: Competitiveness and Globalization (MindTap Course List) (13th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hill, C. W. L., & Jones, G. R. (2011). Essentials of Strategic Management (Available Titles CourseMate) (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Mastering Strategic Management. (2016, January 18). Open Textbooks for Hong Kong.