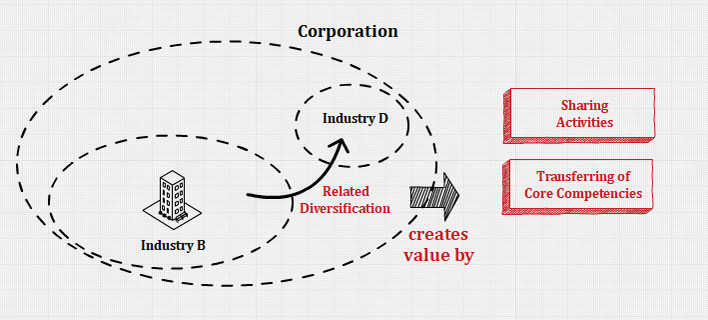

Creating Value with Related Diversification

With the related diversification corporate-level strategy, the firm builds upon or extends its resources and capabilities to build a competitive advantage by creating value for customers.

The company using the related diversification strategy wants to develop and exploit economies of scope between its businesses. In fact, even nonprofit organizations have found that carefully planned and implemented related diversification can create value.

Economies of scope are cost savings a firm creates by successfully sharing resources and capabilities or transferring one or more corporate-level core competencies that were developed in one of its businesses to another of its businesses.

Firms seek to create value from economies of scope through two basic kinds of operational economies: sharing activities (operational relatedness) and transferring corporate-level core competencies (corporate relatedness).

The difference between sharing activities and transferring competencies is based on how separate resources are jointly used to create economies of scope.

To create economies of scope, tangible resources such as plant and equipment or other business-unit physical assets often must be shared. Less tangible resources such as manufacturing know-how and technological capabilities can also be shared.

However, know-how transferred between separate activities with no physical or tangible resource involved is a transfer of corporate-level core competence, not an operational sharing of activities.

Operational Relatedness: Sharing Activities

Firms can create operational relatedness by sharing either a primary activity or a support activity in the value chain. Firms using the related constrained diversification strategy share activities in order to create value.

Activity sharing is risky because ties among a firm’s businesses create links between outcomes. For instance, if demand for one business’s product is reduced, it may not generate sufficient revenues to cover the fixed costs required to operate the shared facilities. These types of organizational difficulties can reduce activity-sharing success.

Additionally, activity sharing requires careful coordination between the businesses involved. The coordination challenges must be managed effectively for the appropriate sharing of activities.

Although activity sharing across businesses is not risk-free, in general, it can create value.

For acquisitions of firms in the same industry (horizontal acquisitions), sharing resources and activities and thereby creating economies of scope contributed to post-acquisition increases in performance and higher returns to shareholders.

Additionally, firms that sold off related units in which resource sharing was a possible source of economies of scope may produce lower returns than those that sold off businesses unrelated to the firm’s core business.

Gaining economies of scope by sharing activities across a firm’s businesses may be important in reducing risk and in creating value. More attractive results are obtained through activity sharing when a strong corporate headquarters office facilitates it.

Corporate Relatedness: Transferring of Core Competencies

Over time, the firm’s intangible resources, such as its know-how, become the foundation of core competencies. Firms seeking to create value through transferring core competencies (corporate relatedness) use the related linked diversification strategy.

Corporate-level core competencies are complex sets of resources and capabilities that link different businesses, primarily through managerial and technological knowledge, experience, and expertise.

The related linked diversification strategy helps firms to create value in at least 2 following ways.

Firstly, because the expense of developing a core competence has already been incurred in one of the firm’s businesses, transferring this competence to a second business eliminates the need for that business to allocate resources to develop it.

Secondly, resource intangibilities are difficult for competitors to understand and imitate. Because of this difficulty, the unit receiving a transferred corporate-level competence often gains an immediate competitive advantage over its rivals.

There are risks related to the implementation of this strategy.

Firstly, one of the ways managers facilitates the transfer of corporate-level core competencies is by moving key people into new management positions. However, the manager of an older business may be reluctant to transfer key people who have accumulated knowledge and experience critical to the business’s success. Thus, managers with the ability to facilitate the transfer of a core competence may come at a premium, or the key people involved may not want to transfer.

Secondly, the top-level managers from the transferring business may not want the competencies transferred to a new business to fulfill the firm’s diversification objectives. Thus, the nature of the top management team can influence the success of the knowledge and skill transfer process. Too much dependence on outsourcing can lower the use of core competencies thereby, reducing their useful transferability to other business units in the diversified firm.

Simultaneous Operational Relatedness and Corporate Relatedness

Some firms simultaneously seek operational and corporate relatedness to create economies of scope.

The ability to simultaneously create economies of scope by sharing activities (operational relatedness) and transferring core competencies (corporate relatedness) is difficult for competitors to understand and learn how to imitate.

However, if the cost of realizing both types of relatedness is not offset by the benefits created, the result is diseconomies because the cost of organization and incentive structure is very expensive.

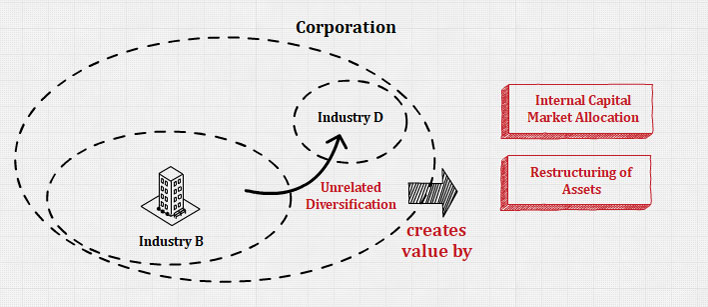

Creating Value with Unrelated Diversification

An unrelated diversification strategy can create value through two types of financial economies. Financial economies are cost savings realized through improved allocations of financial resources based on investments inside or outside the firm.

Efficient internal capital allocations can lead to financial economies. Efficient internal capital allocations reduce risk among the firm’s businesses.

The second type of financial economy concerns the restructuring of acquired assets. Thus, the diversified firm buys another company, restructures that company’s assets in ways that allow it to operate more profitably, and then sells the company for a profit in the external market.

Financial economies rather than either operational or corporate relatedness, are the source of value creation for firms using the unrelated diversification strategy.

Efficient Internal Capital Market Allocation

In a market economy, capital markets are believed to efficiently allocate capital.

Efficiency results as investors take equity positions (ownership) with high expected future cash-flow values. Capital is also allocated through debt as shareholders and debt holders try to improve the value of their investments by taking stakes in businesses with high growth and profitability prospects.

In diversified firms, the corporate headquarters office distributes capital to its businesses to create value for the overall corporation.

The nature of these distributions can generate gains from internal capital market allocations that exceed the gains that would accrue to shareholders as a result of capital being allocated by the external capital market.

Because those in a firm’s corporate headquarters generally have access to detailed and accurate information regarding the actual and potential future performance of the company’s portfolio of businesses, they have the best information to make capital distribution decisions.

Compared with corporate office personnel, external investors have relatively limited access to internal information and can only estimate the performances of individual businesses as well as their future prospects.

Although businesses seeking capital must provide information to potential suppliers, firms with internal capital markets can have at least two informational advantages.

First, the information provided to capital markets through annual reports and other sources emphasizes positive prospects and outcomes. External sources of capital have a limited ability to understand the operational dynamics within large organizations. Even external shareholders who have access to information are unlikely to receive full and complete disclosure.

Second, although a firm must disseminate information, that information also becomes simultaneously available to the firm’s current and potential competitors. Competitors might attempt to duplicate a firm’s value-creating strategy with insights gained by studying such information. Thus, the ability to efficiently allocate capital through an internal market helps the firm protect the competitive advantages it develops while using its corporate-level strategy as well as its various business-level strategies.

If intervention from outside the firm is required to make corrections to capital allocations, only significant changes are possible because the power to make changes by outsiders is often indirect.

External parties can try to make changes by forcing the firm into bankruptcy or changing the top management team. Alternatively, in an internal capital market, the corporate headquarters office can fine-tune its corrections, such as choosing to adjust managerial incentives or encouraging strategic changes in one of the firm’s businesses.

Thus, capital can be allocated according to more specific criteria than is possible with external market allocations. Because it has less accurate information, the external capital market may fail to allocate resources adequately to high-potential investments. The corporate headquarters office of a diversified company can more effectively perform such tasks as disciplining underperforming management teams through resource allocations.

The main challenge associated with using unrelated diversification strategies is that competitors can imitate financial economies more easily than they can replicate the value gained from the economies of scope developed through operational relatedness and corporate relatedness.

Restructuring of Assets

Financial economies can also be created when firms learn how to create value by buying, restructuring, and then selling the restructured companies’ assets in the external market.

As in the real estate business, buying assets at low prices, restructuring them, and selling them at a price that exceeds their cost generates a positive return on the firm’s invested capital. This is a strategy that has been taken up by private equity firms, who buy, restructure and then sell, often within a four or five-year period.

Ideally, executives will follow a strategy of buying businesses when prices are lower, such as in the midst of a recession and selling them at late stages in an expansion.

Because of the increases in global economic activity, including more cross-border acquisitions, there is also a growing number of foreign divestitures and restructuring in internal markets. Foreign divestitures are even more complex than domestic ones and must be managed carefully.

Unrelated diversified companies that pursue this strategy try to create financial economies by acquiring and restructuring other companies’ assets, but it involves significant trade-offs.

In high-technology businesses, resource allocation decisions are highly complex, often creating an information-processing overload on the small corporate headquarters offices that are common in unrelated diversified firms.

In general, high-technology and service businesses are often human-resource dependent. These people can leave or demand higher pay and thus appropriate or deplete the value of an acquired firm.

Buying and then restructuring service-based assets so they can be profitably sold in the external market is also difficult.

Thus, for both high-technology firms and service-based companies, relatively few tangible assets can be restructured to create value and sell profitably. It is difficult to restructure intangible assets such as human capital and effective relationships that have evolved over time between buyers (customers) and sellers (firm personnel).

Resources

Further Reading

Related Concepts

References

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2019). Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases: Competitiveness and Globalization (MindTap Course List) (13th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hill, C. W. L., & Jones, G. R. (2011). Essentials of Strategic Management (Available Titles CourseMate) (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Mastering Strategic Management. (2016, January 18). Open Textbooks for Hong Kong.

- Wheelen, T. L. (2021). Strategic Management and Business Policy: Toward Global Sustainability 13th (thirteenth) edition Text Only. Prentice Hall.