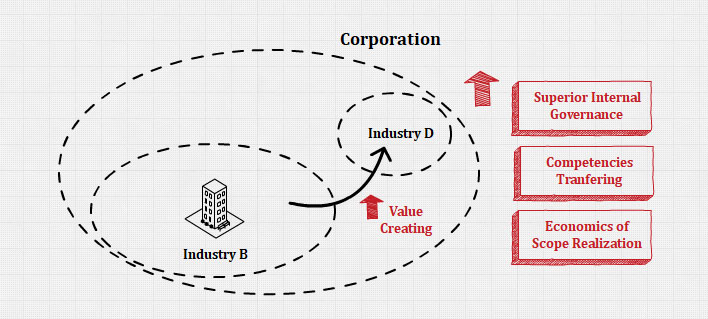

Value-Creating Diversification

Most companies first consider diversification when they are generating financial resources in excess of those necessary to maintain a competitive advantage in their original business or industry. The question strategic managers must tackle is how to invest a company’s excess resources in such a way that they will create the most value and profitability in the long run.

Diversification can help a company create greater value in three main ways: (1) by permitting superior internal governance, (2) by transferring competencies among businesses, and (3) by realizing economies of scope.

Superior Internal Governance

The term internal governance refers to the way the top executives of a company govern its business units, divisions, and functions.

In a diversified company, effective or superior governance revolves around how well top managers can develop strategies that improve the competitive positioning of their business units in the industries where they compete.

Diversification creates value when top managers operate the company’s different business units so effectively that they perform better than they would if they were separate and independent companies.

Certain senior executives develop superior skills in managing and overseeing the operation of many business units and pushing the managers in charge of these business units to achieve high performance.

In general, corporate managers who are successful at creating value through superior internal governance seem to make several similar strategic decisions.

First, they organize the different business units of the company into self-contained divisions each of which operates separately.

Second, these divisions tend to be managed by corporate executives in a highly decentralized fashion. Corporate executives do not get involved in the day-to-day operations of each division. Instead, they set challenging financial goals for each division, probe the general managers of each division about their strategy for attaining these goals, monitor divisional performance, and hold divisional managers accountable for that performance.

Third, corporate managers are careful to link their internal monitoring and control mechanisms to incentive pay systems that reward divisional personnel for attaining, and especially for surpassing, performance goals.

An extension of this approach of creating value through superior internal governance is an acquisition and restructuring strategy.

This strategy involves corporate managers acquiring inefficient and poorly managed enterprises and then creating value by installing their superior internal governance in these acquired companies and restructuring their operations systems to improve their performance.

This strategy can be considered as diversification because the acquired company does not have to be in the same industry as the acquiring company.

The performance of an acquired company can be improved in various ways.

First, the acquiring company usually replaces the top management team of the acquired company with a more aggressive top management team. This team is often drawn from the firm’s own ranks of executives who understand the ways to achieve superior governance.

Second, the new top management team in charge looks for ways to reduce operating costs.

Third, the top management team put in place by the acquiring company then focuses on how the acquired businesses were managed previously and seek out ways to improve the business unit’s efficiency, quality, innovativeness, and responsiveness to customers.

Fourth, in addition, the acquiring company often establishes, for the acquired company, performance goals that cannot be met without significant improvements in operating efficiency. It also makes the new top management aware that failure to achieve performance improvements consistent with these goals within a given amount of time will probably result in losing their jobs.

Fifth, to motivate the new top management team and the other managers of the acquired unit to undertake such demanding and stressful activities, the acquiring company directly links performance improvements in the acquired unit to pay incentives.

This system of rewards and punishments established by the corporate executives of the acquiring company gives the new managers of the acquired business unit every incentive to look for ways of improving the efficiency of the unit under their charge.

Transferring Competencies

A second way for a company to create value from diversification is to transfer its existing distinctive competencies in one or more value creation functions (for example, manufacturing, marketing, materials management, and R&D) to other industries.

Top managers seek out companies in new industries where they believe they can apply these competencies to create value and increase profitability.

They may use the superior skills in one or more of their company’s value creation functions to improve the competitive position of the new business unit. Alternatively, corporate managers may decide to acquire a company in a different industry because they believe the acquired company possesses superior skills that can improve the efficiency of their existing value creation activities.

If successful, such competency transfers can lower the costs of value creation in one or more of a company’s diversified businesses or enable one or more of these businesses to perform their value creation functions in a way that leads to differentiation and a premium price.

For such a strategy to work, the competencies being transferred must allow the acquired company to establish a competitive advantage in its industry. That is, they must confer a competitive advantage on the acquired company.

Economies of Scope

Economies of scope can reduce the total operating costs when two or more business units can share resources or capabilities such as manufacturing facilities, distribution channels, advertising campaigns, and R&D costs.

Each business unit that shares a common resource has to pay less to operate a particular functional activity. This resource sharing has given both business units a cost advantage that has enabled them to undercut the prices of their less diversified competitors.

Like competency transfers, diversification to realize economies of scope is possible only if there is a real opportunity for sharing the skills and services of one or more of the value-creation functions between a company’s existing and new business units.

Diversification, for this reason, should be pursued only when sharing is likely to generate a significant competitive advantage in one or more of a company’s business units. Moreover, managers need to be aware that the costs of managing and coordinating the activities of the newly linked business units to achieve economies of scope are substantial and may outweigh the value that can be created by such a strategy.

Thus, just as in the case of vertical integration, the costs of managing and coordinating the skill and resource exchanges between business units increase substantially as the number and diversity of its business units increase.

This places a limit on the amount of diversification that can profitably be pursued. It makes sense for a company to diversify only if the extra value created by such a strategy exceeds the increased costs associated with incorporating additional business units into a company. Many companies diversify past this point, acquiring too many new companies, and their performance declines.

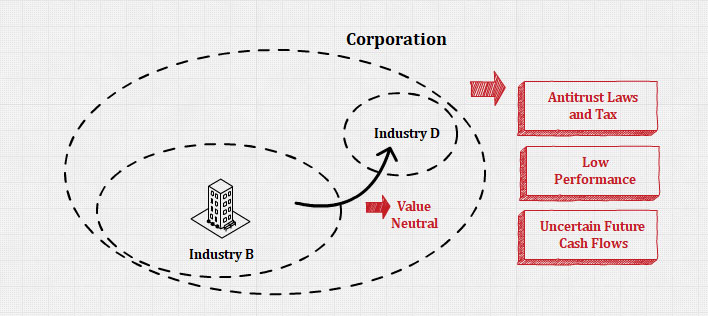

Value-Neutral Diversification

The objectives firms seek when using related diversification and unrelated diversification strategies all have the potential to help the firm create value through the corporate-level strategy.

However, these strategies, as well as single- and dominant-business diversification strategies, are sometimes used with objectives that are value-neutral. Different incentives to diversify sometimes exist, and the quality of the firm’s resources may permit only diversification that is value-neutral rather than value-creating.

Incentives to diversify come from both the external environment and a firm’s internal environment.

External incentives include antitrust regulations and tax laws. Internal incentives include low performance, uncertain future cash flows, and the pursuit of synergy, and reduction of risk for the firm.

Antitrust Regulation and Tax Laws

Antitrust laws prohibiting mergers that created increased market power (via either vertical or horizontal integration) were stringently enforced during that period.

The tax effects of diversification stem not only from corporate tax changes but also from individual tax rates. Some companies generate more cash from their operations than they can reinvest profitably. Sometimes free cash flows should be redistributed to shareholders as dividends. However, depending on tax effects, if the firm’s stock value appreciated over the long term, shareholders might receive a better return on those funds than if the funds had been redistributed as dividends because returns from stock sales would be taxed more lightly than would dividends.

Corporate tax laws also affect diversification.

Acquisitions typically increase a firm’s depreciable asset allowances. Increased depreciation (a non-cash-flow expense) produces lower taxable income, thereby providing an additional incentive for acquisitions. Thus, regulatory changes create incentives or disincentives for diversification.

Low Performance

In general, low returns are related to greater levels of diversification. If high performance eliminates the need for greater diversification, then low performance may provide an incentive for diversification.

Firms, which have an incentive to diversify, need to be careful because often there are brand risks to moving into areas that are new and where the company lacks operational expertise. There can be negative synergy (where the potential synergy between acquiring and target firms is illusory) and problems between leaders and cultural fit difficulties with recent acquisitions.

In general, an overall curvilinear relationship may exist between diversification and performance. Although low performance can be an incentive to diversify, firms that are more broadly diversified compared to their competitors may have overall lower performance.

Uncertain Future Cash Flows

As a firm’s product line matures or is threatened, diversification may be an important defensive strategy.

Small firms and companies in mature or maturing industries sometimes find it necessary to diversify for long-term survival. Diversifying into other product markets or into other businesses can reduce the uncertainty about a firm’s future cash flows.

Synergy and Firm Risk Reduction

Diversified firms pursuing economies of scope often have investments that are too inflexible to realize synergy among business units.

Synergy exists when the value created by business units working together exceeds the value that those same units create working independently. However, as a firm increases its relatedness among business units, it also increases its risk of corporate failure because synergy produces joint interdependence among businesses that constrains the firm’s flexibility to respond.

This threat may force two basic decisions.

First, the firm may reduce its level of technological change by operating in environments that are more certain. This behavior may make the firm risk-averse and thus uninterested in pursuing new product lines that have potential but are not proven. Alternatively, the firm may constrain its level of activity sharing and forgo the potential benefits of synergy.

Either or both decisions may lead to further diversification.

Operating in environments that are more certain will likely lead to related diversification into industries that lack less potential, while constraining the level of activity sharing may produce additional, but unrelated, diversification, where the firm lacks expertise.

In general, a firm using a related diversification strategy is more careful in bidding for new businesses, whereas a firm pursuing an unrelated diversification strategy may be more likely to overbid because it is less likely to have full information about the firm it wants to acquire.

However, firms using either a related or an unrelated diversification strategy must understand the consequences of paying large premiums. Alternatively, diversified firms (related and unrelated) can be innovative if the firm pursues these strategies appropriately.

These dynamic problems often cause managers to become more risk-averse and focus on achieving short-term returns. When this occurs, managers are less likely to be concerned about social problems and in making long-term investments.

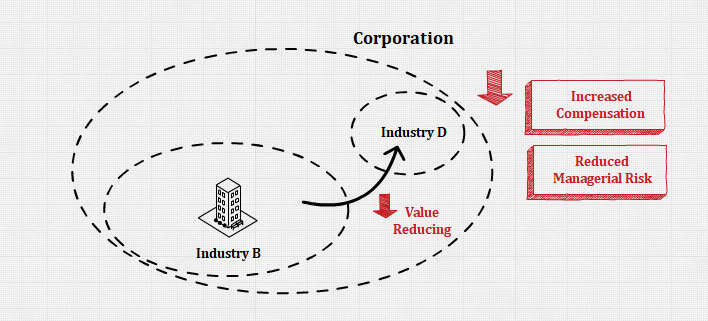

Value-Reducing Diversification

The desire for increased compensation and reduced managerial risk are two motives for top-level executives to diversify their firm beyond value-creating and value-neutral levels.

Diversification provides additional benefits to top-level managers that shareholders do not enjoy. Diversification and firm size are highly correlated, and as firm size increases, so does executive compensation.

Because large firms are complex, difficult-to-manage organizations, top-level managers commonly receive substantial levels of compensation to lead them, but the amounts vary across countries. Greater levels of diversification can increase a firm’s complexity, resulting in still more compensation for executives to lead an increasingly diversified organization.

Governance mechanisms, such as the board of directors, monitoring by owners, executive compensation practices, and the market for corporate control, may limit managerial tendencies to over diversify.

In some instances, though, a firm’s governance mechanisms may not be strong, allowing executives to diversify the firm to the point that it fails to earn even average returns.

The loss of adequate internal governance may result in relatively poor performance, thereby triggering a threat of takeover. Therefore, an external governance threat, although restraining managers, does not flawlessly control managerial motives for diversification.

Most large publicly held firms are profitable because the managers leading them are positive stewards of firm resources, and many of their strategic actions, including those related to selecting a corporate-level diversification strategy, contribute to the firm’s success.

Governance mechanisms should be designed to deal with exceptions to the managerial norms of making decisions and taking actions that increase the firm’s ability to earn above-average returns. Thus, it is overly pessimistic to assume that managers usually act in their own self-interest as opposed to their firm’s interest.

Top-level executive’s diversification decisions may also be held in check by concerns for their reputation. If a positive reputation facilitates the development and use of managerial power, a poor reputation can reduce it. Likewise, a strong external market for managerial talent may deter managers from pursuing inappropriate diversification.

In addition, a diversified firm may acquire other firms that are poorly managed in order to restructure its own asset base. Knowing that their firms could be acquired if they are not managed successfully encourages executives to use value-creating diversification strategies.

The level of diversification with the greatest potential positive effect on performance is based partly on the effects of the interaction of resources, managerial motives, and incentives on the adoption of particular diversification strategies.

The greater the incentives and the more flexible the resources, the higher the level of expected diversification. Financial resources (the most flexible) should have a stronger relationship to the extent of diversification than either tangible or intangible resources. Tangible resources (the most inflexible) are useful primarily for related diversification.

Firms can improve their strategic competitiveness when they pursue a level of diversification that is appropriate for their resources (especially financial resources) and core competencies and the opportunities and threats in their country’s institutional and competitive environments.

Resources

Further Reading

Related Concepts

References

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2019). Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases: Competitiveness and Globalization (MindTap Course List) (13th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hill, C. W. L., & Jones, G. R. (2011). Essentials of Strategic Management (Available Titles CourseMate) (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Mastering Strategic Management. (2016, January 18). Open Textbooks for Hong Kong.