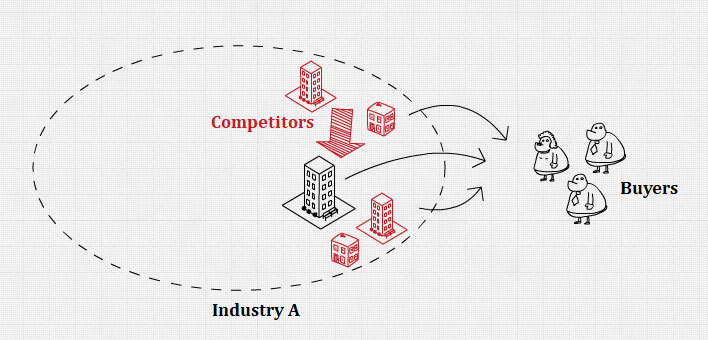

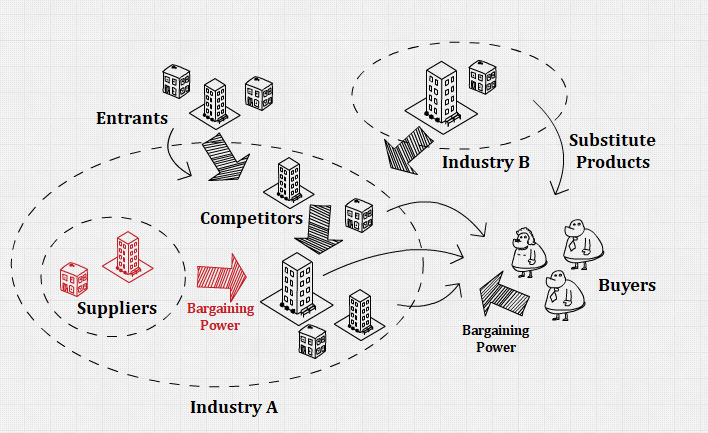

One of the most recognized theories in industry analysis of micro-environment is the five forces competitive model of Michael Porter.

This model gives insight to firms in understanding the competitive landscape that they are facing within the micro-environment.

The model consists of 5 forces: (1) rivalry among existing firms, (2) threat of new entrants, (3) threat of substitute products or services, (4) bargaining power of buyers, and (5) bargaining power of suppliers.

Force 1: Rivalry among Existing Firms

Rivalry refers to the competitive struggle between companies in an industry to gain market share from each other.

The competitive struggle can be fought using price, product design, advertising and promotion spending, direct selling efforts, after-sales service and support, and innovation. More recently, firms begin to speed a new product to the market to gain a competitive advantage.

Firms within industries are rarely homogeneous. They differ in resources and capabilities and seek to differentiate themselves from competitors. Typically, firms seek to differentiate their products from competitors’ offerings in ways that customers value and in which the firms have a competitive advantage.

The competitive rivalry intensifies when a firm is challenged by a competitor’s actions or when a company recognizes an opportunity to improve its market position. The strategies pursued by one firm can be successful only to the extent that they provide a competitive advantage over the strategies pursued by rival firms.

Because an industry’s firms are mutually dependent, actions that are taken by one company usually invite responses. Changes in strategy by one firm may be met with retaliatory countermoves, such as lowering prices, enhancing quality, adding features, providing services, extending warranties, and increasing advertising.

The rivalry also increases when (1) consumers can switch brands easily; (2) when barriers to leaving the market are high; (3) when fixed costs are high; (4) when the product is perishable; (5) when consumer demand is growing slowly or declines such that rivals have excess capacity and/or inventory; (6) when the products being sold are commodities; (7) when rival firms are diverse in strategies, origins, and culture; and (8) when mergers and acquisitions are common in the industry.

Intense rivalry among established companies constitutes a strong threat to profitability.

More intense rivalry implies lower prices or more spending on non-price-competitive weapons, or both. Because intense rivalry lowers prices and raises costs, it squeezes profits out of an industry.

Alternatively, if rivalry is less intense, companies may have the opportunity to raise prices or reduce spending on non-price- competitive weapons, which leads to a higher level of industry profits.

As rivalry among competing firms intensifies, industry profits decline, in some cases to the point where industry becomes inherently unattractive. When rival firms sense weakness, typically they will intensify both marketing and production efforts to capitalize on the opportunity.

The intensity of rivalry among competing firms tends to increase as the number of competitors increases, as competitors become more equal in size and capability, as demand for the industry’s products declines, and as price-cutting becomes common.

The intensity of rivalry among established companies within an industry is largely a function of 4 factors.

These factors are (1) industry competitive structure, (2) industry demand conditions, (3) cost conditions, and (4) exit barrier conditions in the industry.

Factor 1: Industry Competitive Structure

The competitive structure of an industry refers to the number and size distribution of companies in it.

Industry structures vary, and different structures have different implications for the intensity of rivalry.

Intense rivalries are common in industries with many companies. With multiple competitors, it is common for a few firms to believe they can act without eliciting a response. However, other firms generally are aware of competitors’ actions, often choosing to respond to them.

At the other extreme, industries with only a few firms of equivalent size and power also tend to have strong rivalries. The large and often similar-sized resource bases of these firms permit vigorous actions and responses.

There are 2 primary structures: (1) a fragmented industry, and (2) a consolidated industry.

A fragmented industry consists of a large number of small- or medium-sized companies, none of which is in a position to determine industry price.

Many fragmented industries are characterized by low entry barriers and commodity-type products that are hard to differentiate. The combination of these traits tends to result in boom-and-bust cycles as industry profits rise and fall. Low entry barriers imply that whenever demand is strong and profits are high, new entrants will flood the market, hoping to profit from the boom.

Often the flood of new entrants into a booming fragmented industry creates excess capacity, so companies start to cut prices in order to use their spare capacity. The difficulty companies face when trying to differentiate their products from those of competitors can exacerbate this tendency. The result is a price war, which depresses industry profits, forces some companies out of business, and deters potential new entrants.

Most booms are relatively short-lived because of the ease of new entry and will be followed by price wars and bankruptcies. Because it is often difficult to differentiate products in these industries, the best strategy for a company is to try to minimize its costs so it will be profitable in a boom and survive any subsequent bust.

In general, the more commodity-like an industry’s product is, the more vicious will be the price war. This bust part of the cycle continues until overall industry capacity is brought into line with demand, at which point prices may stabilize again.

A fragmented industry structure, then, constitutes a threat rather than an opportunity for a firm operating within that industry.

A consolidated industry is dominated by a small number of large companies (an oligopoly), or in extreme cases, by just one company (a monopoly) in which companies often are in a position to determine industry prices.

Companies might try to adopt strategies that change the underlying structure of fragmented industries and lead to a consolidated industry structure in which the level of industry profitability is increased.

In consolidated industries, companies are interdependent, because one company’s competitive actions or moves (with regard to price, quality, and so on) directly affect the market share of its rivals, and thus their profitability. When one company makes a move, this generally forces a response from its rivals, and the consequence of such competitive interdependence can be a dangerous competitive spiral.

Rivalry increases as companies attempt to undercut each other’s prices or offer customers more value in their products, pushing industry profits down in the process.

Companies in consolidated industries sometimes seek to reduce this threat by following the prices set by the dominant company in the industry. However, companies must be careful, for explicit face-to-face price-fixing agreements are illegal. Legal activities are tacit or indirect agreements, arrived at without direct or intentional communication. Instead, companies set prices by watching, interpreting, anticipating, and responding to each other’s behavior.

Factor 2: Industry Demand Conditions

Growing demand from new customers or additional purchases by existing customers tend to moderate competition by providing greater scope for companies to compete for customers.

When a market is growing, firms try to effectively use resources to serve an expanding customer base. Growing demand tends to reduce rivalry because all companies can sell more without taking market share away from other companies.

Markets increasing in size reduce the pressure to take customers from competitors. High industry profits are often the result.

In no-growth or slow-growth markets, rivalry becomes more intense as firms battle to increase their market shares by attracting competitors’ customers. Declining demand results in more rivalry as companies fight to maintain market share and revenues.

The instability in the market that results from these competitive engagements may reduce the profitability for all firms engaging in such battles.

Demand declines when customers are leaving the marketplace or each customer is buying less. Now a company can grow only by taking market share away from other companies.

Thus, declining demand constitutes a major threat for it increases the extent of rivalry between established companies.

Factor 3: Cost Conditions

In industries where fixed costs are high, profitability tends to be highly leveraged to sales volume, and the desire to grow volume can spark off intense rivalry.

Fixed costs refer to the costs that must be covered before the firm makes a single sale.

When fixed costs account for a large part of total costs, companies try to maximize the use of their productive capacity. Doing so allows the firm to spread costs across a larger volume of output.

However, when many firms attempt to maximize their productive capacity, excess capacity is created on an industry-wide basis. If sales volume is low firms cannot cover their fixed costs and they will not be profitable.

This creates an incentive for firms to cut their prices and/or increase promotion spending in order to drive up sales volume, thereby covering fixed costs. However, doing this often intensifies competition.

The pattern of excess capacity at the industry level followed by intense rivalry at the firm level is frequently observed in industries with high storage costs.

In situations where demand is not growing fast enough and too many companies are engaged in the same actions, cutting prices and/or raising promotion spending in an attempt to cover fixed costs, the result can be intense rivalry and lower profits.

Factor 4: Exit Barriers Conditions

Exit barriers are economic, strategic, and emotional factors that prevent companies from leaving an industry.

Sometimes companies continue competing in an industry even though the returns on their invested capital are low or even negative. Firms making this choice likely face high exit barriers causing them to remain in an industry when the profitability of doing so is questionable.

The result is often excess productive capacity, which leads to even more intense rivalry and price competition as companies cut prices in the attempt to obtain the customer orders needed to use their idle capacity and cover their fixed costs.

The 6 common exit barriers are as follows.

The first is, government and social restrictions based on converse for job losses and regional economic effects.

The second is, economic dependence on the industry because a company relies on a single industry for its revenue and profit.

The third is strategic interrelationships of mutual dependence between one business and other parts of a company’s operations, including share facilities and access to financial markets.

The fourth is emotional attachments to industry, as when a company’s owners or employees are unwilling to exit from industry for sentimental reasons or because of pride.

The fifth is investments in specialized assets such as specific machines, equipment, and operating facilities that are of little or no value in alternative uses or cannot be sold off. These are assets with a value linked to a particular business or location. If a company wishes to leave the industry, it has to write off the book value of these assets.

The sixth is high fixed costs of exit, such as the severance pay, health benefits, labor benefits, and pensions that have to be paid to workers who are being made redundant when a company ceases to operate.

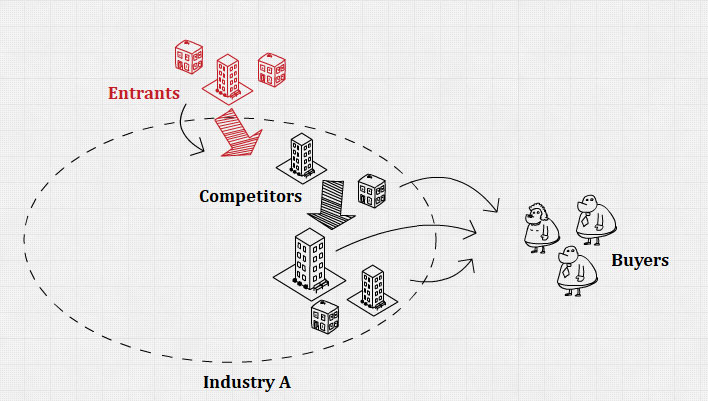

Force 2: Threat of New Entrants

Potential competitors are companies that are not currently competing in the industry but have the capability to do so.

Whenever new firms can easily enter a particular industry, the intensity of competitiveness among firms increases. They are threats to established organizations within the industry.

Identifying new entrants is important because they can threaten the market share of existing competitors.

The height of barriers to entry is one of the most important determinants of profit rates in the industry. Clearly, it is in the interest of established companies to pursue strategies consistent with raising entry barriers to secure these profits. By the same token, potential new entrants have to find strategies that allow them to circumvent barriers to entry. The best way to do this is not to compete head-to-head with incumbents, but to look for customers who are poorly served by incumbents, and to go after those customers using new distribution channels and new business models.

One reason new entrants pose such a threat is that they bring additional production capacity. Unless the demand for a good or service is increasing, additional capacity holds consumers’ costs down, resulting in less revenue and lower returns for competing firms. Often, new entrants have a keen interest in gaining a large market share. As a result, new competitors may force existing firms to be more efficient and to learn how to compete in new dimensions.

Therefore, established companies already operating in an industry often attempt to discourage potential competitors from entering the industry because the more companies that enter, the more difficult it becomes for established companies to protect their share of the market and generate profits.

The likelihood that firms will enter an industry is a function of two factors: barriers to entry and the retaliation expected from current industry participants. Entry barriers make it difficult for new firms to enter an industry and often place them at a competitive disadvantage even when they are able to enter. As such, high entry barriers tend to increase the returns for existing firms in the industry and may allow some firms to dominate the industry. Thus, firms competing successfully in the industry want to maintain high entry barriers in order to discourage potential competitors from deciding to enter the industry.

An entry barrier is an obstruction that makes it difficult for a company to enter the industry.

The risk of entry by potential competitors is a factor that makes it costly for companies to enter an industry. A high risk of entry by potential competitors represents a threat to the profitability of established companies. If the risk of new entry is low, established companies can take advantage of this opportunity to raise prices and earn greater returns.

The threat of entry depends on the presence of entry barriers and expected reaction from existing competitors. The greater the costs that potential competitors must bear to enter an industry, the greater are the barriers to entry and the weaker this competitive force. High entry barriers may keep potential competitors out of an industry even when industry profits are high.

There are different kinds of barriers to entering a market to consider when examining an industry environment. Companies competing within a particular industry study these barriers to determine the degree to which their competitive position reduces the likelihood of new competitors being able to enter the industry to compete against them. Firms considering entering an industry should study entry barriers to determine the likelihood of being able to identify an attractive competitive position within the industry.

Some of the possible entry barriers include (1) economies of scale, (2) product differentiation, (3) capital requirements, (4) customer switching costs, (5) access to distribution channels, (6) cost disadvantages independent of size, (7) government policy, (8) technology and specialized know-how, (9) customer loyalty, (10) brand preferences, (11) access to raw materials, (12) possession of patents, (13) undesirable locations, (14) potential saturation of the market, and (15) government regulation.

Despite numerous barriers to entry, new firms sometimes enter industries with higher-quality products, lower prices, and substantial marketing resources.

These new entrants to the industry generally bring new capacity and substantial resources.

Existing firms, therefore, need to identify potential new firms entering the market, monitor the new rival firms’ strategies, counterattack as needed, and capitalize on existing strengths and opportunities.

When the threat of new firms entering the market is strong, incumbent firms generally fortify their positions and take actions to deter new entrants, such as lowering prices, extending warranties, adding features, or offering financing specials.

Entry Barrier 1: Economies of Scale

Economies of scale arise when unit costs fall as a firm expands its output.

Economies of scale are derived from incremental efficiency improvements through experience as a firm grows larger. Therefore, the cost of producing each unit declines as the quantity of a product produced during a given period increases. A new entrant is unlikely to quickly generate the level of demand for its product that in turn would allow it to develop economies of scale.

Economies of scale can be developed in most business functions, such as marketing, manufacturing, research and development, and purchasing. Firms sometimes form strategic alliances or joint ventures to gain scale economies.

If the cost advantages from economies of scale are significant, a new company that enters the industry and produces on a small scale suffers a significant cost disadvantage relative to established companies.

If the new company decides to enter on a large scale in an attempt to obtain these economies of scale, it has to raise the capital required to build large-scale production facilities and bear the high risks associated with such an investment.

A further risk of large-scale entry is that the increased supply of products will depress prices and result in vigorous retaliation by established companies. For these reasons, the threat of entry is reduced when established companies have economies of scale.

Sources of scale economies include (1) cost reductions gained through mass-producing a standardized output, (2) discounts on bulk purchases of raw material inputs and component parts, (3) the advantages gained by spreading fixed production costs over a large production volume, and (4) the cost savings associated with spreading marketing and advertising costs over a large volume of output.

Some competitive conditions reduce the ability of economies of scale to create an entry barrier such as the use of scale-free resources, or mass customization.

Many companies now customize their products for large numbers of small customer groups. In these cases, customized products are not manufactured in the volumes necessary to achieve economies of scale. Customization is made possible by several factors including flexible manufacturing systems.

In fact, the new manufacturing technology facilitated by advanced information systems has allowed the development of mass customization in an increasing number of industries. Online ordering has enhanced customers’ ability to buy customized products. Companies manufacturing customized products can respond quickly to customers’ needs in lieu of developing scale economies.

Entry Barrier 2: Brand Loyalty

Brand loyalty exists when consumers have a preference for the products of established companies.

A company can create brand loyalty through continuous advertising of its brand name products and company name, patent protection of products, product innovation achieved through company research and development programs, an emphasis on high product quality, and good after-sales service.

Significant brand loyalty makes it difficult for new entrants to take market share away from established companies. Thus, it reduces the threat of entry by potential competitors since they may see the task of breaking down well-established customer preferences as too costly.

Entry Barrier 3: Absolute Cost Advantages

Sometimes, established companies have an absolute cost advantage relative to potential entrants. It means that entrants cannot expect to match the established companies’ lower cost structure.

Proprietary product technology, favorable access to raw materials, desirable locations, and government subsidies are examples. The successful competition requires new entrants to reduce the strategic relevance of these factors.

In general, if established companies have an absolute cost advantage, the threat of entry as a competitive force is weaker.

Absolute cost advantages arise from three main sources (1) superior production operations and processes due to accumulated experience in the industry, patents, or secret processes; (2) control of particular inputs required for production, such as labor, materials, equipment, or management skills, that are limited in their supply; and (3) access to cheaper funds because existing companies represent lower risks than new entrants, and therefore face a lower cost of capital.

Entry Barrier 4: Customer Cost Switching

Costs switching arises when it costs a customer time, energy, and money to switch from the products offered by one established company to the products offered by a new entrant.

In short, switching costs are the one-time costs customers incur when they buy from a different supplier. The costs of buying new equipment and of retraining employees, and even the psychological costs of ending a relationship, maybe incurred in switching to a new supplier. Switching costs can also vary as a function of time.

Occasionally, a decision made by manufacturers to produce a new, innovative product creates high switching costs for customers. If switching costs are high, a new entrant must offer either a substantially lower price or a much better product to attract buyers. When switching costs are high, customers can be locked into the product offerings of established companies, even if new entrants offer better products. Usually, the more established the relationships between parties, the greater the switching costs.

If established companies have built brand loyalty for their products, have an absolute cost advantage with respect to potential competitors, have significant economies of scale, are the beneficiaries of high switching costs, or enjoy regulatory protection, the risk of entry by potential competitors is greatly diminished.

This situation presents a weak competitive force. Consequently, established companies can charge higher prices, and industry profits are higher.

Entry Barrier 5: Product Differentiation

Over time, customers may come to believe that a firm’s product is unique.

This belief can result from the firm’s service to the customer, effective advertising campaigns, or being the first to market a good or service. When customers find a differentiated product that satisfies their needs, they frequently purchase the product loyally over time. Greater levels of perceived product uniqueness create customers who consistently purchase a firm’s products.

Industries with many companies that have successfully differentiated their products have less rivalry, resulting in lower competition for individual firms and higher returns. To combat the perception of uniqueness, new entrants frequently offer products at lower prices. This decision, however, may result in lower profits or even losses.

Entry Barrier 6: Capital Requirement

Competing in a new industry requires a firm to have resources to invest.

In addition to physical facilities, capital is needed for inventories, marketing activities, and other critical business functions. Even when a new industry is attractive, the capital required for successful market entry may not be available to pursue the market opportunity.

Entry Barrier 7: Access to Distribution Channels

Over time, industry participants commonly learn how to effectively distribute their products. After building a relationship with its distributors, a firm will nurture it, thus creating switching costs for the distributors.

Access to distribution channels can be a strong entry barrier for new entrants, particularly in consumer nondurable goods industries and in international markets.

New entrants have to persuade distributors to carry their products, either in addition to or in place of those currently distributed. Price breaks and cooperative advertising allowances may be used for this purpose. However, those practices reduce the new entrant’s profit potential. Interestingly, access to distribution is less of a barrier for products that can be sold on the Internet.

Entry Barrier 8: Government Policy

Through their decisions about issues such as the granting of licenses and permits, governments can control entry into an industry.

Also, governments often restrict entry into some industries because of the need to provide quality service or the desire to protect jobs.

It is not uncommon for governments to attempt to regulate the entry of foreign firms, especially in industries considered critical to the country’s economy or important markets within it. Governmental decisions and policies regarding antitrust issues also affect entry barriers.

Entry Barrier 9: Expected Retaliation

Companies seeking to enter an industry also anticipate the reactions of firms in the industry.

An expectation of swift and vigorous competitive responses reduces the likelihood of entry. Vigorous retaliation can be expected when the existing firm has a major stake in the industry, when it has substantial resources, and when industry growth is slow or constrained.

Locating market niches not being served by incumbents allows the new entrant to avoid entry barriers. Small entrepreneurial firms are generally best suited for identifying and serving neglected market segments.

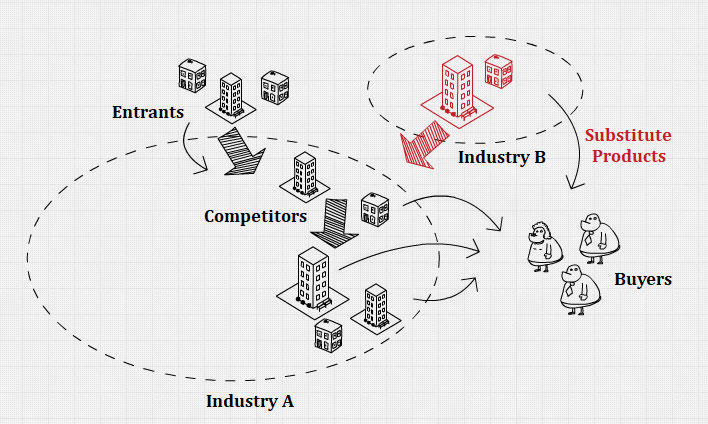

Force 3: Threat of Substitute Products or Services

In many industries, firms are in close competition with producers of substitute products in other industries.

Substitute products are goods or services from outside a given industry that perform similarly or the same functions as a product that the industry produces. It is a product that appears to be different but can satisfy the same need as another product. The presence of substitute products puts a ceiling on the price that can be charged before consumers will switch to the substitute product. Price ceilings equate to profit ceilings and more intense competition among rivals. If switching costs are low, substitutes may have strong effects on an industry.

The identification of possible substitute products or services means searching for products and services that can perform the same function and nurture the same needs for customers, even though they have a different appearance and may not be easily substitutable.

Competitive pressures arising from substitute products increase as the relative price of substitute products declines and as consumers’ switching costs decrease. The competitive strength of substitute products is best measured by the inroads into the market share those products obtain, as well as those firms’ plans for increased capacity and market penetration.

The magnitude of competitive pressure derived from the development of substitute products is generally evidenced by rivals’ plans for expanding production capacity, as well as by their sales and profit growth numbers.

The existence of close substitutes is a strong competitive threat because this limits the price that companies in one industry can charge for their product, and thus industry profitability.

If an industry’s products have few close substitutes so that substitutes are a weak competitive force, then, other things being equal, companies in the industry have the opportunity to raise prices and earn additional profits.

In general, product substitutes present a strong threat to a firm when customers face few if any switching costs and when the substitute product’s price is lower or its quality and performance capabilities are equal to or greater than those of the competing product. Differentiating a product along dimensions that are valuable to customers (such as quality, service after the sale, and location) reduces a substitute’s attractiveness.

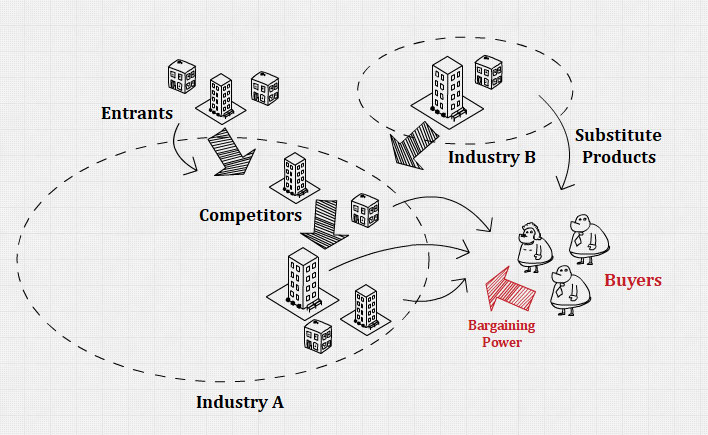

Force 4: Bargaining Power of Buyers

When buyers are concentrated or large or buy in volume, their bargaining power represents a major force affecting the intensity of competition in an industry.

Buyers affect an industry through their ability to drive the prices, bargain for higher quality and services, and place competitors against each other.

An industry’s buyers may be the individual customers who ultimately consume its products (its end users) or the companies that distribute an industry’s products to end-users, such as retailers and wholesalers.

The bargaining power of buyers refers to the ability of buyers to bargain down prices charged by companies in the industry or to raise the costs of companies in the industry by demanding better product quality and service.

Firms seek to maximize the return on their invested capital. Alternatively, buyers want to buy products at the lowest possible price, the point at which the industry earns the lowest acceptable rate of return on its invested capital.

By lowering prices and rising costs, powerful buyers can bargain for higher quality, greater levels of service, lower prices, and thus squeeze profits out of an industry. These outcomes are achieved by encouraging competitive battles among the industry’s firms. Thus, powerful buyers should be viewed as a threat. Alternatively, when buyers are in a weak bargaining position, companies in an industry can raise prices, and perhaps reduce their costs by lowering product quality and service, and increase the level of industry profits.

Rival firms may offer extended warranties or special services to gain customer loyalty whenever the bargaining power of consumers is substantial. The bargaining power of buyers also is higher when the products being purchased are standard or undifferentiated. When this is the case, consumers often can negotiate the selling price, warranty coverage, and accessory packages to a greater extent.

The bargaining power of buyers can be the most important force affecting competitive advantage.

Buyers gain increasing bargaining power under the following circumstances: (1) a buyer purchases a large proportion of the sellers’ products and services, (2) a buyer has a potential to integrate backward by entering the industry, producing the product itself, and thus supply their own needs, (3) the industry composes of many small companies, thus alternative suppliers are plentiful; while buyers are large and few in number, (4) a buyer can economically switch to competing brands or substitutes because switching costs are low, (5) product represents a high percentage of a buyer’s cost, thus providing an incentive to switch product for a lower price, (6) a buyer earns low profits and is very sensitive to costs and service differences, (7) product is unimportant to the final quality or price of a buyer’s products and services, and (8) buyers are armed with great amounts of information about the product costs.

Force 5: Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Suppliers affect an industry through their ability to raise prices or reduce the quality of purchased goods and services.

Suppliers are the organizations that provide inputs into the industry, such as materials, services, and labor (which may be individuals, organizations such as labor unions, or companies that supply contract labor). The bargaining power of suppliers refers to the ability of suppliers to raise input prices or to raise the costs of the industry in other ways.

The bargaining power of suppliers affects the intensity of competition in an industry, especially when there is a large number of suppliers, when there are only a few good substitute raw materials, or when the cost of switching raw materials is especially costly.

Powerful suppliers squeeze profits out of an industry by raising the costs of companies in the industry. Thus, powerful suppliers are a threat. Alternatively, if suppliers are weak, companies in the industry have the opportunity to force down input prices and demand higher quality input. As with buyers, the ability of suppliers to make demands on a company depends on their power relative to that of the company.

In general, a supplier or group of suppliers is powerful in the following situations: (1) supplier industry is dominated by a few large companies, but it sells to many; (2) purchasing industry would experience significant switching costs if they moved to products and services of different suppliers, thus the company depends on a particular supplier and cannot play suppliers off against each other to reduce the price; (3) its product or service is unique and vital to the companies in an industry, while satisfactory substitutes are not readily available; (4) suppliers are able to enter their customers’ industry, use their inputs to produce products and services, thus they integrate forward and compete directly with their customers; (5) purchasing industry buys only a small portion of the supplier group’s goods and services and is unimportant to the supplier, thus the profitability of suppliers is not significantly affected; and (6) companies in the industry cannot threaten to integrate backward, enter their suppliers’ industry and make their own inputs as a tactic for lowering the price of inputs.

Firms may pursue a backward integration strategy to gain control or ownership of suppliers. This strategy is especially effective when suppliers are unreliable, too costly, or not capable of meeting a firm’s needs on a consistent basis. Firms generally can negotiate more favorable terms with suppliers when backward integration is a commonly used strategy among rival firms in an industry. However, in many industries, it is more economical to use outside suppliers of component parts than to self-manufactured the items.

In more and more industries, sellers are forging strategic partnerships with select suppliers in efforts to (1) reduce inventory and logistics costs; (2) speed the availability of next-generation components; (3) enhance the quality of the parts and components being supplied and reduce defect rates; and (4) squeeze out important cost savings for both themselves and their suppliers.

Increasing prices and reducing the quality of their products are potential means suppliers use to exert power over firms competing within an industry. If a firm is unable to recover cost increases by its suppliers through its own pricing structure, its profitability is reduced by its suppliers’ actions.

Some buyers attempt to manage or reduce suppliers’ power by developing a long-term relationship with them. Although long-term arrangements reduce buyer power, they also increase the suppliers’ incentive to be helpful and cooperative in appreciation of the longer-term relationship (guaranteed sales). This is especially true when the partners develop trust in one another.

It is often in the best interest of both suppliers and producers to assist each other with reasonable prices, improved quality, development of new services, just-in-time deliveries, and reduced inventory costs, thus enhancing long-term profitability for all concerned.

Resources

Further Reading

- Porter’s Five Forces of Competitive Position Analysis (cgma.org)

- The Five Forces (isc.hbs.edu)

- Industry analysis and competition: Porter’s five forces (learn.marsdd.com)

- Porter’s 5 Forces (investopedia.com)

Related Concepts

References

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2016). Strategic Management: Concepts: Competitiveness and Globalization (12th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2019). Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases: Competitiveness and Globalization (MindTap Course List) (13th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hill, C. W. L., & Jones, G. R. (2011). Essentials of Strategic Management (Available Titles CourseMate) (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Mastering Strategic Management. (2016, January 18). Open Textbooks for Hong Kong.

- Wheelen, T. L. (2021). Strategic Management and Business Policy: Toward Global Sustainability 13th (thirteenth) edition Text Only. Prentice Hall.