Directional Type 1: Growth Strategies

What is a Growth Strategy?

In general, companies must grow to survive. Continuing growth means increases in sales and reduction in the cost of products sold, thereby increasing profits.

A corporation can grow internally by expanding its operations both globally and domestically, or it can grow externally through mergers, acquisitions, and strategic alliances.

Reasons to Use Growth Strategy

The first reason is that growth based on increasing market demand may mask organizational flaws that would otherwise be visible in a stable or declining market. A growing flow of revenue will create organizational slack that is unused resources to help resolve internal organization problems between departments or divisions. Large firms also have more bargaining power than do small firms.

The second reason is that growing firms offer more opportunities for advancement, promotion, and interesting jobs. Growth is viewed positively by the marketplace and investors. Executive compensation tends to be bigger as an organization increases in size. Large organizations are less likely to be acquired, which makes executive jobs in these firms more secure.

Types of Growth Strategies

There are 2 main types of growth strategies, (1) concentration and (2) diversification.

Growth Strategy 1: Concentration

A company uses concentration strategies to focus its resources and capabilities on competing successfully within the confines of a particular product market.

A concentration strategy is important in fast-growing industries that make strong demands on a company’s resources and capabilities but also offer the prospect of substantial long-term profits if a company can sustain its competitive advantage.

There are several advantages to concentrating on the needs of customers in just one product market (and the different segments within it).

A major advantage of concentrating on a single industry is that doing so enables a company to focus all its managerial, financial, technological, and functional resources and capabilities on developing strategies to strengthen its competitive position in just one business.

Concentrating on a single business allows a company to focus on doing what it knows best and avoid entering new businesses it knows little about and where it can create little value. This prevents companies from becoming involved in businesses that their managers do not understand and where poor, uninformed decision-making can result in huge losses.

In fact, fast-growing companies that spread their resources too thin, in order to compete in several different product markets, run the risk of starving their core business of the resources needed to expand rapidly. The result is a loss of competitive advantage in the core business.

Many mature companies that expand over time into too many different businesses and markets find out later that they have stretched their resources too far and that their performance declines as a result.

Concentrating on just one market or industry may also result in disadvantages emerging over time.

Being concentrating too much on industry would result in a considerable amount of vertical integration to strengthen a company’s competitive advantage within its core industry.

Moreover, companies that concentrate on just one industry may miss out on opportunities to create more value and increase their profitability by using their resources and capabilities to make and sell products in other markets or industries.

There are 3 concentration strategies.

They are (1) market penetration, which involves trying to gain an additional share of a firm’s existing markets using existing products; (2) market development, which involves taking existing products and trying to sell them within new markets; and (3) product development, which involves creating new products to serve existing markets.

A firm can use one, two, or all three as part of its efforts to excel within an industry.

There are 2 main types of concentration strategies. They are (1) vertical integration, and (2) horizontal integration.

Growth Strategy 2: Diversification

Firms use diversification strategies to focus on developing other product lines in other industries.

Directional Type 2: Stability Strategies

When to Use Stability Strategy?

Stability strategies can be appropriate for a successful corporation operating in a reasonably predictable environment. They can be very useful in the short run but can be dangerous if followed for too long.

A corporation may choose stability instead of growth by continuing its current activities without any significant change in direction.

Types of Stability Strategies

Some of the most popular strategies are the pause/proceed-with-caution, no-change, and profit strategies.

Stability Strategy 1: Pause/Proceed-with-caution

This can be viewed as an opportunity to rest before continuing a growth or retrenchment strategy. The organization attempt to make only incremental improvements until a particular environmental situation changes.

It is a temporary strategy to be used until the environment becomes more hospitable or to enable a company to consolidate its resources after prolonged rapid growth.

Stability Strategy 2: No-change

This is a decision to do nothing new and to continue current operations and policies for a foreseeable future. The relative stability encourages the company to continue its current courses with only small adjustments for inflation or profit objectives.

The firm is enjoying a reasonably profitable and stable niche for its products. There are no obvious opportunities or threats, nor is there much to signify strengths or weaknesses. Unless the external environment changes and the industry is undergoing consolidation, the company is likely to keep following a no-change strategy.

Stability Strategy 3: Profit

This is a decision to do nothing new in a worsening situation but instead to act as though the problems organization is facing are only temporary. Blaming the problems on a hostile environment such as government policies or unethical competitors, management defers investments and cuts expenses to stabilize profits during this period.

This strategy is useful only to help a company get through a temporary difficulty. This strategy can deteriorate the competitive position of the firm in long term. This strategy is more suitable only for short-term responses to difficult situations.

Directional Type 3: Retrenchment Strategies

What is a Retrenchment Strategy?

Trench warfare inspired the business term retrenchment. Firms following a retrenchment strategy shrink one or more of their business units.

Much like an army under attack, firms using this strategy hope to make just a small retreat rather than losing a battle for survival.

A company may pursue retrenchment strategies when it has a weak competitive position in some or all of its product lines, and that sales are down and profits are becoming losses.

Retrenchment is often most accomplished through laying off employees. This is a common rationale for retrenchment, that by shrinking the size of a firm, executives hope that the firm can survive as a profitable enterprise.

Types of Retrenchment Strategies

In an attempt to eliminate the weaknesses that are dragging the organization down, management may follow several of the following retrenchment strategies.

Retrenchment Strategy 1: Turnaround

Turnaround occurs when an organization regroups through cost and asset reduction to reverse declining sales and profits. It is designed to fortify an organization’s basic distinctive competence.

During the turnaround, management works with limited resources and faces pressure from shareholders, employees, and the media. This strategy emphasizes the improvement of operational efficiency and it is most appropriate when the problems are pervasive but not yet critical.

Turnaround can entail selling off land and buildings to raise needed cash, pruning product lines, closing marginal businesses, closing obsolete factories, automating processes, reducing the number of employees, and instituting expense control systems.

There are 5 guidelines that make turnaround an especially effective strategy for firms to pursue.

They are as follows: (1) When an organization has a clearly distinctive competence but has failed consistently to meet its objectives and goals over time; (2) When an organization is one of the weaker competitors in a given industry; (3) When an organization is plagued by inefficiency, low profitability, poor employee morale, and pressure from stockholders to improve performance; (4) When an organization has failed to capitalize on external opportunities, minimize external threats, take advantage of internal strengths, and overcome internal weaknesses over time; and (5) When an organization has grown so large so quickly that major internal reorganization is needed.

Retrenchment Strategy 2: Downsizing

Downsizing is a reduction in the number of a firm’s employees and, sometimes, in the number of its operating units; but, the composition of businesses in the company’s portfolio may not change through downsizing.

Thus, downsizing is an intentional managerial strategy that is used for the purpose of improving firm performance.

In general, downsizing may be of more tactical (or short-term) value than strategic (or long-term) value, meaning that firms should exercise caution when restructuring through downsizing.

Downsizing can be an appropriate strategy to use after completing an acquisition, particularly when there are significant operational and/or strategic relationships between the acquiring and the acquired firm.

In these instances, the newly formed firm may have excess capacity in functional areas such as sales, manufacturing, distribution, human resource management, and so forth. In turn, excess capacity may prevent the combined firm from realizing anticipated synergies and the reduced costs associated with them.

One of the limitations of downsizing is that it typically does not lead to higher firm performance.

The stock markets generally evaluate downsizing negatively, believing that it has long-term negative effects on the firms’ efforts to achieve strategic competitiveness. Investors also seem to conclude that downsizing occurs as a consequence of other problems in a company. This assumption may be caused by a firm’s diminished corporate reputation when a major downsizing is announced.

Another limitation of downsizing is that it can lead to the loss of human capital.

Losing employees with many years of experience with the firm represents a major loss of knowledge. Knowledge is vital to competitive success in the global economy. A loss of valuable human capital can also spill over into dissatisfaction with customers. Thus, downsizing is far more effective when they consistently use human resource practices that ensure procedural justice and fairness in downsizing decisions, so that it can minimize the loss of valuable human capital.

There are 2 basic phases of a downsizing strategy. They are contraction and consolidation.

Contraction is an across-the-board cutback in size and costs. Jobs are cut during this phase.

Consolidation is a program to stabilize the now-leaner corporation. Plans are developed to reduce unnecessary overhead and to make functional activities cost-justified. An overemphasis on downsizing and cutting costs coupled with a heavy hand by top management is usually counterproductive and can actually hurt performance. If all employees are encouraged to get involved in productivity improvements, the firm is likely to emerge from this retrenchment period to a much better and strong company.

Retrenchment Strategy 3: Captive Company

This strategy involves giving up independence in exchange for security. Management desperately searches for a larger company in order to guarantee the company’s continued existence with a long-term contract.

In this way, the corporation may be able to reduce the scope of some of its functional activities and thus significantly reducing costs. The weaker company gains certainty of sales and production in return for becoming heavily dependent on another firm for a large share of its sales.

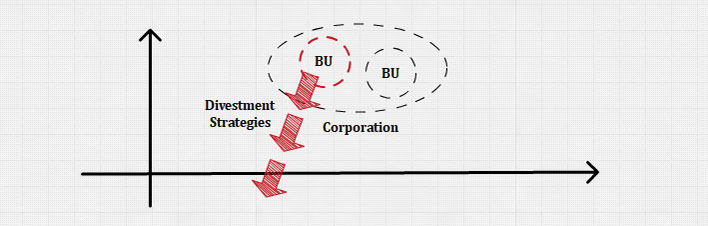

Directional Type 4: Restructure Strategies

What is a Restructure Strategy?

Restructuring is a strategy through which a firm changes its set of businesses or its financial structure.

Historically, divesting businesses from company portfolios have accounted for a large percentage of firms’ restructuring strategies. Commonly, firms focus on fewer products and markets following restructuring.

Although restructuring strategies are generally used to deal with acquisitions that are not reaching expectations, firms sometimes use restructuring strategies because of changes they have detected in their external environment.

Reasons to Use Restructuring Strategies

Failed Acquisitions: Restructuring can also be a response to failed acquisitions.

This is true whether the acquisitions were made to support a horizontal integration, vertical integration, or diversification strategy.

Diversification Discount: Another reason why extensively diversified companies restructure is that the stock market has assigned a diversification discount to the stock price.

Diversification discount refers to the fact that the stock of highly diversified companies is often assigned a lower valuation relative to their earnings than the stock of less diversified companies.

There are two reasons for this.

First, investors are often put off by the complexity and lack of transparency in the financial statements of highly diversified enterprises that are harder to interpret and may not give them a good picture of how the individual divisions of the company are performing. In other words, they perceive diversified companies as riskier investments than companies that focus on one or a few major industries. In such cases, restructuring can boost the returns to shareholders when it splits the company into a number of parts that can each be divested at a higher price.

A second reason for the diversification discount is that many investors have learned from experience that managers often have a tendency to pursue too much diversification or to diversify for the wrong reasons, such as the pursuit of growth for its own sake, rather than to increase profitability. Some senior managers tend to expand the scope of their company beyond the point where the bureaucratic costs of managing extensive diversification exceed the additional value that can be created so that the performance of the company begins to decline. Restructuring in such cases is often a response to declining financial performance.

Advanced Innovations: A final factor that helps to explain why restructuring is occurring more and more frequently is because of innovations in management strategy and in advanced IT.

These elements have diminished the profit-enhancing advantages of vertical integration and diversification. So, to increase profitability, companies have reduced the scope of their activities through restructuring and exiting businesses.

Restructure Strategy 1: Divestment/Downscoping

Divestment is when the organization has multiple business units and product lines, and it chooses to sell off a division.

Divestment often is used to raise capital for further strategic acquisitions or investments.

It can be part of an overall strategy to rid an organization of businesses that are unprofitable, that require too much capital, or that do not fit well with the firm’s other activities.

Divestment has also become a popular strategy for firms to focus on their core businesses. Managerial effectiveness increases because the firm has become less diversified, allowing the top management team to better understand and manage the remaining businesses.

In some cases, divestment reverses a forward vertical integration strategy. Divestment can also be used to reverse backward vertical integration. Divestment also serves as a means to undo diversification strategies. Divestment can be especially appealing to executives in charge of firms that have engaged in unrelated diversification.

Divestment generally leads to more positive outcomes in both the short and long term. Its desirable long-term outcome of higher performance is a product of reduced debt costs and the emphasis on strategic controls derived from concentrating on the firm’s core businesses. The hope is that the company can then reach a higher level of profitability and cut back on product lines that the organization no longer has resources and capabilities to pursue.

Divestment involves selling a business unit to the highest bidder. Three types of buyers are independent investors, other companies, and the management of the unit to be divested.

Selling off a business unit to independent investors is normally referred to as a spinoff. A spinoff makes good sense when the unit to be sold is profitable and when the stock market has an appetite for new stock issues. However, spinoffs do not work if the unit to be spun off is unprofitable and unattractive to independent investors or if the stock market is slumping and unresponsive to new issues.

Selling off a unit to another company is a strategy frequently pursued when a unit can be sold to a company in the same line of business as the unit. The hope is that the new company will have the necessary resources and capabilities to turn the organization profitable. The purchaser is often prepared to pay a considerable amount of money for the opportunity to substantially increase the size of its business virtually overnight.

There are 6 guidelines that make divestment an especially effective strategy for firms to pursue.

They are as follows: (1) When an organization has pursued a retrenchment strategy and failed to accomplish needed improvements; (2) When a division needs more resources to be competitive than the company can provide; (3) When a division is responsible for an organization’s overall poor performance; (4) When a division is a misfit with the rest of an organization; this can result from radically different markets, customers, managers, employees, values, or needs; (5) When a large amount of cash is needed quickly and cannot be obtained reasonably from other sources; and (6) When government antitrust action threatens an organization.

Restructure Strategy 2: Leveraged Buyouts

A leveraged buyout (LBO) is a restructuring strategy whereby a party (typically a private equity firm) buys all of a firm’s assets in order to take the firm private. Once a private equity firm completes this type of transaction, the target firm’s company stock is no longer traded publicly.

Traditionally, leveraged buyouts were used as a restructuring strategy to correct for managerial mistakes or because the firm’s managers were making decisions that primarily served their own interests rather than those of shareholders

However, some firms complete leveraged buyouts for the purpose of building firm resources and expanding their operations rather than simply restructuring a distressed firm’s assets.

Significant amounts of debt are commonly incurred to finance a buyout. To support debt payments and to downscope the company to concentrate on the firm’s core businesses, the new owners may quickly sell a number of assets.

There are 3 types of LBOs: management buyouts (MBOs), employee buyouts (EBOs), and whole-firm buyouts.

In part because of managerial incentives, MBOs, more so than EBOs and whole-firm buyouts, have been found to lead to increased strategic focus and improved performance.

MBOs can lead to greater entrepreneurial activity and growth. As such, buyouts can represent a form of firm rebirth to facilitate entrepreneurial efforts and stimulate strategic growth and productivity.

Whole-firm LBOs have been hailed as a significant innovation in the financial restructuring of firms.

However, this type of restructuring can be complicated, especially when cross-border transactions are involved.

Moreover, they can involve negative trade-offs. First, the resulting large debt increases the firm’s financial risk. Sometimes, the intent of the owners to increase the efficiency of the acquired firm and then sell it within five to eight years creates a short-term and risk-averse managerial focus. As a result, these firms may fail to invest adequately in R&D or take other major actions designed to maintain or improve the company’s ability to compete successfully against rivals.

Because buyouts more often result in significant debt, most LBOs have been completed in mature industries where stable cash flows are the norm. Stable cash flows support the purchaser’s efforts to service the debt obligations assumed as a result of taking a firm privately.

Directional Type 5: Exit Strategies

Types of Exit Strategies

Companies can choose from three main strategies for exiting business areas: harvest, bankruptcy, and liquidation.

Exit Strategy 1: Harvest

A harvest strategy involves halting investment in a unit in order to maximize short-to-medium-term cash flow from that unit.

Although this strategy seems fine in theory, it is often a poor one to apply in practice. Once it becomes apparent that the unit is pursuing a harvest strategy, the morale of the unit’s employees, as well as the confidence of the unit’s customers and suppliers in its continuing operation, can sink very quickly.

If this occurs, as it often does, the rapid decline in the unit’s revenues can make the strategy untenable.

Exit Strategy 2: Bankruptcy/Liquidation

This strategy happens in the worst possible situation with the organization having a poor competitive position with few prospects. Because no one is interested in buying a weak company in an unattractive industry, the firm must pursue bankruptcy or liquidation.

Bankruptcy involves giving up management to the courts in return for some settlement of the organization’s obligations.

The hope is that once the court decides the claims on the company, it will be stronger and better able to compete in a more attractive industry.

Liquidation involves termination of the operations of a business unit because the industry is unattractive and/or the business unit is too weak to be sold as a going concern.

A pure liquidation strategy is the least attractive of all to pursue, because it requires that the company write off its investment in a business unit, often at considerable cost. Management may choose to convert as many saleable assets as possible to cash, which is then distributed to the shareholders after all obligations are paid.

Liquidation is a recognition of defeat and consequently can be an emotionally difficult strategy. However, it may be better to cease operating than to continue losing large sums of money.

There are 3 guidelines that make liquidation an especially effective strategy for firms to pursue.

They are as follows: (1) When an organization has pursued a retrenchment strategy, especially a divestment/divestiture strategy, and has not been successful; (2) When an organization’s only alternative is bankruptcy. Liquidation represents an orderly and planned means of obtaining the greatest possible cash for an organization’s assets; and (3) When the stockholders of a firm can minimize their losses by selling the organization’s assets.

Resources

Further Reading

- A Complete Guide to Directional Strategy (welpmagazine.com)

- Complete Guide to Corporate Directional Strategy (welpmagazine.com)

- Three Directional Business Strategies (bizfluent.com)

Related Concepts

- Corporate Level Strategy

- Vertical Integration Growth Strategies

- Horizontal Integration Growth Strategies

- Basic Concepts of Diversification Strategies

References

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2016). Strategic Management: Concepts: Competitiveness and Globalization (12th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2019). Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases: Competitiveness and Globalization (MindTap Course List) (13th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hill, C. W. L., & Jones, G. R. (2011). Essentials of Strategic Management (Available Titles CourseMate) (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning.